Last week, the only noise louder than jet engines at large U.S. airports were the raucous demonstrators protesting one of President Trump’s recent Executive Orders, this one suspending immigration from seven majority Muslim countries, along with potential changes to the vetting process for newcomers.

Among the many concerns about the policy is the issue of local interpreters in these countries. These men and women are usually locals who greatly assist US forces and are given preferential treatment when it comes to immigration. They put themselves in great danger – sometimes much greater danger than the military personnel they assist.

Members of the military have raised the concern that this Executive Order will not only create barriers for those who should gain immediate entry, but will also reduce the likely pool of new interpreters. Based upon my experience, this is a valid concern. After all, if you and I were in their situation, we would almost certainly avoid risking our lives on behalf of a country that doesn’t appear to want us to live there.

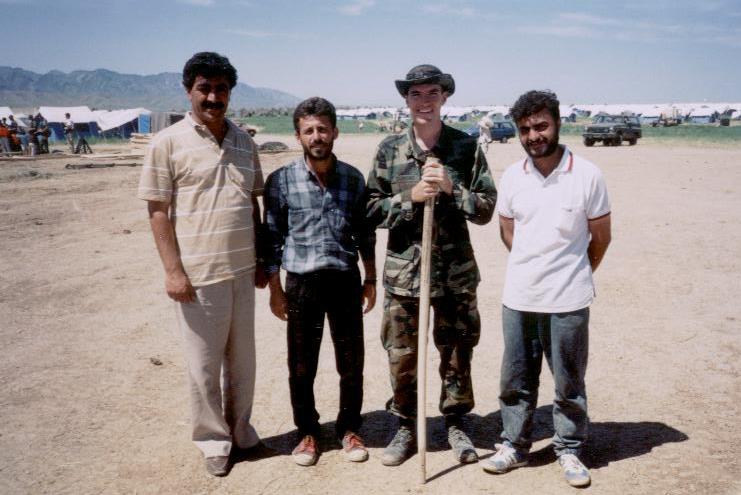

I spent approximately six months in Kuwait and Iraq in 1991, and although the current interpreter issue is more closely tied to the post 9/11 wars in Iraq, Afghanistan and elsewhere, I thought I’d introduce you to two of the interpreters I spent the most time with during Operation Desert Storm, where I was in Kuwait City, and Operation Provide Comfort, where I was in Northern Iraq.

Although I worked with a few interpreters in Kuwait City, the interpreter I spent most of my time with was Mohammad. Mohammad was part of a really smart program someone in the government thought of (and how often can we say that?). The military had a need for interpreters who were familiar with Kuwait City, and they figured out where a lot of potential candidates were hanging out: on the campuses of American universities. Mohammad was a faculty member at Kansas State, and everywhere I went, he was with me.

People usually only think about the language translation when they hear the word “interpreter”, but in reality their knowledge of local geography and customs is every bit as important. During the Iraqi occupation, one of the many ways that the local Kuwaitis harassed the occupying troops was by pulling down all the street signs. This was a great idea until we arrived. This was the pre-GPS era, so we had to use satellite maps and vector our way toward our various objectives. Mohammad was indispensable as he knew how his boyhood city was laid out, which somewhat helped compensate for his unending singing of the first lines from the song “The Age of Aquarias” while we were together.

But the closest relationship I had by far with Ahmed, my Kurdish interpreter while we were in Northern Iraq as part of the humanitarian relief effort after Desert Storm. I don’t remember how Ahmed acquired his language skills since I know he hadn’t been anywhere other than Iraq, but he and I spent most of our waking hours together. He helped me in a number of ways, from establishing a working relationship with the various elders and power-brokers in the Kurdish culture, to helping track down the parents of a lost child (it’s easy to get lost in a refugee camp when you’re six).

Ahmed had relatives in Sweden and I know he was trying to figure out how to escape Iraq. When I left, I wrote a note for Ahmed to present to any State Department or US military officials he might encounter in hopes he could parlay that into a good job, or even a ticket to U.S. citizenship.

It felt like a cheap and insufficient “thank you” from our nation, but it was the only option available at the time.

I often think of the many interpreters that have made vital contributions to our country since 9/11. Although most of them have never been to the United States, in many ways they are some of the finest Americans you could hope to meet. I expect our country to loudly and clearly honor our immigration commitments to them and their families.